Message given at Durham Friends Meeting, May 21, 2023

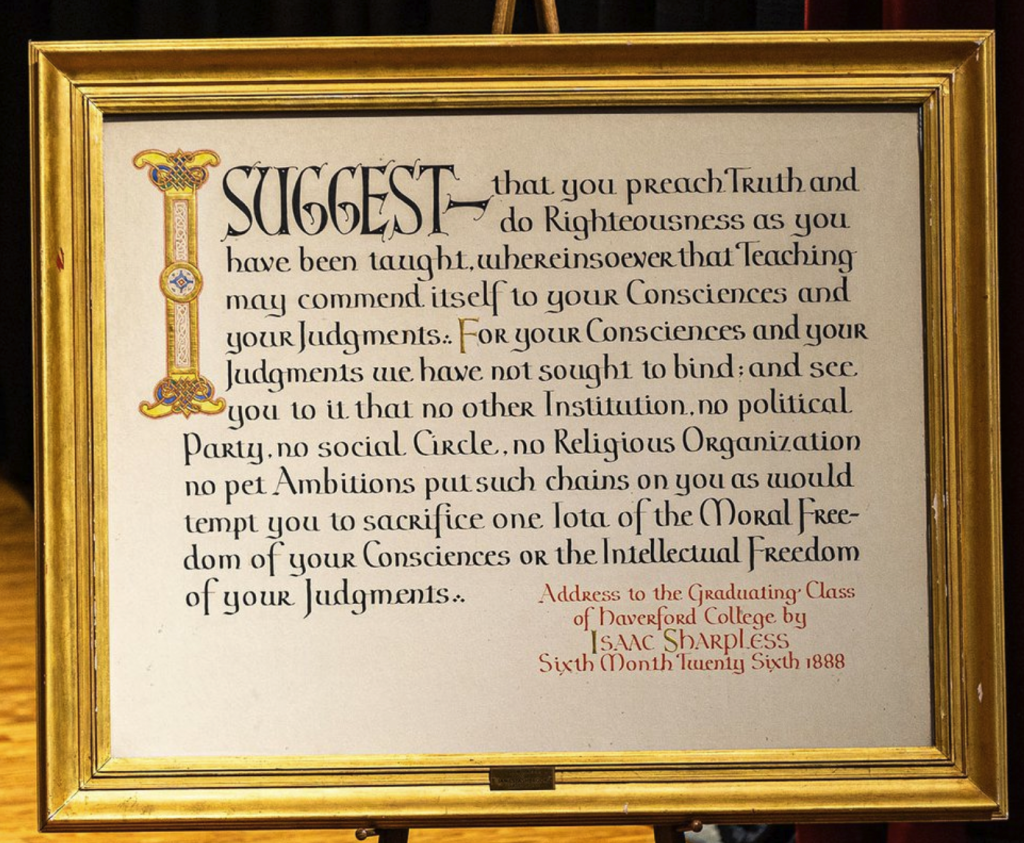

I was first introduced to Quakerism as a student at Haverford College. One way I received that first introduction was a quotation in ornate script (unusually ornate for Quakerism) that hung in the Common Room. It was from a Commencement Address in 1883 by Isaac Sharpless, then the college president, in 1883. It reads:

“I suggest that you preach truth and do righteousness as you have been taught, whereinsoever that teaching may commend itself to your consciences and your judgements. For your consciences and your judgments we have not sought to bind; and see you to it that no other institution, no political party, no social circle, no religious organizations, no pet ambitions put such chains on you as would tempt you to sacrifice one iota of the moral freedom of your consciences or the intellectual freedom of your judgements.”

I’m not the only Haverfordian who was struck by those words. I know several who carry it around in their wallets, or have copies of that inscription in their homes.

I’m no longer sure that this Isaac Sharpless quotation is a good introduction to Quakerism. For me, it speaks too much of individualism, of conscience and freedom, and not enough of worship or God’s will, or of community for that matter.

Nevertheless, that injunction to “preach truth and do righteousness” laid a heavy stamp on me and it still speaks to me. It’s an active exhortation. These are positive things to do, things to do actively, not things to avoid, not things to stay silent upon. “Preach truth and do righteousness.” It’s an urging to be wholly and fully yourself, to stand for what you believe, and to enact those beliefs in the world in every way that you can. “Preach truth and do righteousness,” or, as another Quaker once put it, “Let your life speak.”

That Sharpless quotation mostly warns against the constraints that others may place on our inclination to say or do the right thing – political parties, say, or religious organizations. But over the years I’ve been more struck by the constraints we place on ourselves. The ways we hold ourselves back – hold ourselves back from doing the right thing. We do nothing. We stay silent and seated rather than “preach truth and do righteousness.” We pay attention to what’s ‘in our interest’ or what’s ‘comfortable’ for us. Mostly what holds us back is loving ourselves more than loving our neighbors.

Today, I see a lot of people standing around doing nothing. Bad things happen, and lots of people step backwards or they sit down. In current parlance, they ‘ghost.’ “It’s not mine to do anything about,” they seem to be saying. “Maybe this will soon blow over.” “I’m not getting involved.” “I don’t think I want to get drawn into this.” Maybe we roll our eyes or look away when lies are told. Down that road, what’s the truth of things becomes murky, and we all grow cynical in the belief that everyone cuts corners, and no one does anything about it.

The currently popular list of Quaker testimonies follows a SPICES mnemonic: simplicity, peace, integrity, community, equality, stewardship. It’s “Integrity” I want to lift up today, and there it is in the middle of the SPICES list.

That list makes it one of six, but Wilmer Cooper wrote a Pendle Hill pamphlet in which he said “’integrity’ is the essential Quaker testimony and undergirds all other testimonies of Friends.” (PH 296, p 6). (Wilmer was the founding Dean of the Earlham School of Religion and someone who, along with his wife Emily, Ellen and I had the privilege to know.) I think he’s right; integrity is the essential Quaker testimony.

He opens the Pendle Hill pamphlet by telling a story about Elfrida Vipont Foulds, a distinguished British Quaker and historian, going to the village of Fenney Drayton, where George Fox had grown up, to see if she could better understand what shaped him. She sat in the church where he worshipped as a child – an Anglican Church of course. And she forms a picture of men and women coming week after week on Sunday, religiously. And then she says “But the self-same people would go from the church the following week cheating their neighbors, cheating in the marketplace, they would get drunk in the ale houses; husbands would beat their wives and parents would cuff their children. Next Sunday they would go back to the village church….”. (p 4). The taproot for Fox, she concluded, is that “Fox felt the need for integrity in daily life.”

This makes sense. For me, integrity is the essential Quaker testimony.

The word integrity evolved from the Latin adjective integer, meaning whole or complete. The word has come to mean “an undivided or unbroken completeness.” And with regard to our behavior, it has come to mean “soundness of moral principle and character; entire uprightness or fidelity, especially in regard to truth and fair dealing”.

Here are a few things it asks of us.

Integrity means speaking the truth of course. It asks for honesty through and through. In the Sermon on the Mount, Jesus tells us:

37 But let [a]your ‘Yes’ be ‘Yes,’ and your ‘No,’ ‘No.’ For whatever is more than these is from the evil one” (Matthew 5:37).

Early Friends –and Friends today – refuse to swear oaths, because to swear an oath before making a statement implies that this time I’m telling the truth, but at other times, maybe not.

It is not just being truthful in what you do say, but also in having the courage to speak up, and to tell the whole truth that you know, even when that’s painful. Just knowing the truth isn’t good enough; you have to tell others. You have to make that an unwavering practice and habit. Speak the truth at all times, but also: step forward to be of assistance. Don’t ‘leave it to others.’ If you won’t speak up, who will?

Integrity means standing up as well as speaking up – standing up for others. It means being actively engaged when others are wronged. I’m sure you can all think of instances of wrongdoing that we later learn others knew about and yet stayed silent. That’s not integrity. Speaking up about wrongdoing has become rare enough that we’ve coined a word to describe those who do: “whistleblower.” But often we realize many people knew about the wrongdoing, and only one or two spoke up – and maybe not immediately. That’s not integrity. When someone ‘blows the whistle,’ ask yourself who hasn’t said a word. We rarely need whistleblowers if the rest of us will speak up in the first place.

Integrity means treating everyone the same, not treating some more favorably because they have power or can provide benefits to you. Early Friends were known for having just one price for all customers. Integrity today means caring for everyone, not just ourselves or our allies or our friends.

Integrity means caring for others as well as yourself. It means treating others with ‘unreserved respect’ – as if they, too, were hosts for a Divine presence within. It means loving your neighbors as much as yourself. Loving our neighbors means not just comforting them in private but stepping forward in public for them on their behalf. It means standing up for others – all others.

In A Christmas Carol, Scrooge is a man who is all about his business – in every way, every hour of every day. He thinks Christmas is a humbug; he thinks charity is absurd. But by the end he is a man transformed. He is a joyful man celebrating Christmas, and also now a man of integrity. Dickens has Scrooge say about “his business” now that he is a reformed man:”

“Mankind was my business. The common welfare was my business; charity, mercy, forbearance, benevolence, were all my business. The dealings of my trade were but a drop of water in the comprehensive ocean of my business!” Scrooge goes from being a man who stays put in his counting house to someone who steps forward to help others.

Integrity asks that we be trustworthy: good to our word, consistent, reliable, always, in private and in public, indoors and out. When I was a Boy Scout, we would regularly recite the Scout Law: “A Scout is trustworthy, loyal, helpful, friendly, courteous, kind, obedient, cheerful, thrifty, brave, clean and reverent.” It’s a list of twelve, but it begins with “trustworthy,” reminding us to live by the other eleven always and consistently. It gives the others strength.

Speaking up, standing up, treating everyone with respect, with fairness, with caring; being trustworthy; that’s what integrity asks of us. It’s a lot. Sometimes, maybe often, it means taking steps away from comfort.

We speak of “faithfulness” as central to our relationship to God. In a parallel way, “integrity” is central in our relationships with other people. Both mean doing what we should be doing, doing it actively, doing it wholeheartedly, with no holding back.

What does integrity ask of us? Everything. To have integrity means ‘being whole,’ and that means embracing the whole of things, not just your corner of things. It means to live a life in which we are fully present – whole, wholly yourself, wholly present. It means living as if you lived in the new kingdom. When Fox says (and this is a cornerstone of the peace testimony) “I told them I lived in the virtue of that life and power that taketh away the occasion for war,” he means he went the whole way in his obedience to God, not part way. He inhabited the new kingdom with his whole self as if he were a tent pole.

To have integrity means being part of the backbone of how all things should be. Integrity is the essential Quaker testimony because it gives voice and strength to all the others. It means standing up for and supporting the way all things should be. The other testimonies – simplicity, peace, community, equality, stewardship – mean very little without integrity to give them backbone.

Or, as Isaac Sharpless instructed: “preach truth and do righteousness.”

+++

Pingback: Integrity, the Backbone of the Testimonies | River View Friend