[Or, We’re Slipping Again into a Time of Religious War]

Message given at Durham Friends Meeting, November 12, 2023

It is tolerance that is on my mind this morning. Tolerance isn’t one of the Testimonies of Friends, and perhaps it should not be so considered, but still it has an importance for Friends.

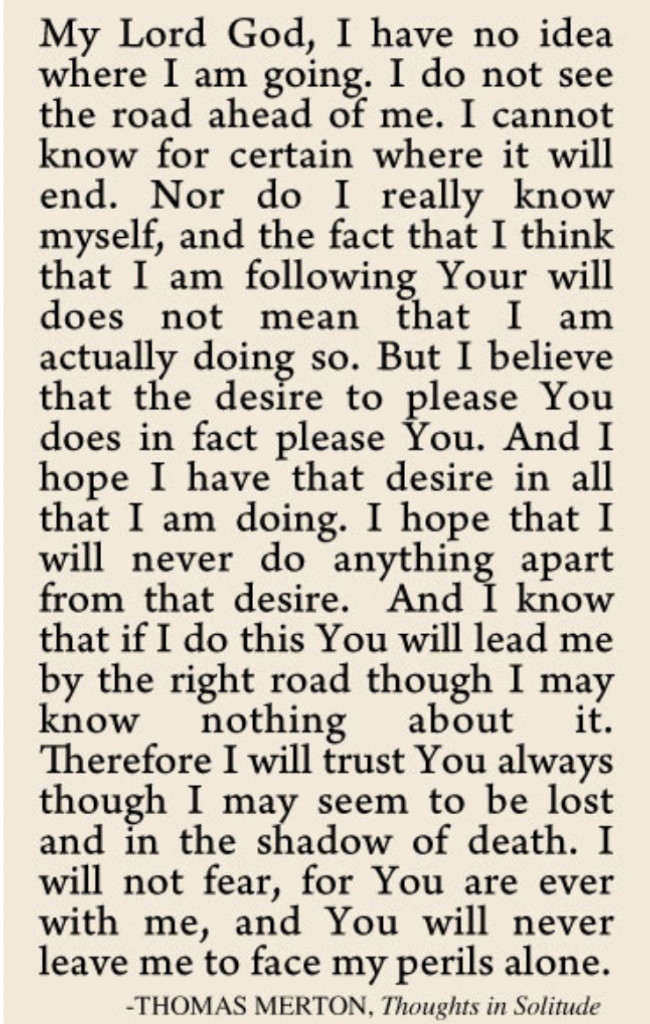

Wouldn’t it be wonderful if all of us agreed about everything? Wouldn’t that be splendid – a harmony. A peace, you might say. I don’t mean we’d all agree about the little things, like which flavor of ice cream is best, or whether the Patriots are our favorite team.

I mean wouldn’t it be great if we all agreed about the big questions like what is the proper name of God, or how should God be worshipped or what is sinful in the eyes of God and what is not. Wouldn’t agreement on those matters be heavenly? Surely in heaven there is nothing but agreement.

Or would it? Maybe you can think of some reasons this might not be so good. Maybe you can think of reasons this would be hard to achieve without conflict or violence. Humans can find it hard to agree with one another; that seems to be just the way we are. Sometimes people try to force others to believe what they believe, to achieve that uniform harmony of belief. And that conflict can be painful. It can become religious war – war to achieve heaven on earth.

Today, I’ve been thinking we are slipping again into a time of religious war – or something very like it. Conflict, yes, but “religious”? Is that the right word? That may strike you as an odd thing to say. In the United States many fewer people consider themselves religious than just a few decades ago. The same is true in Europe and in much of Asia and Latin America.

Nevertheless, around the world we have religious wars between Jews and Muslims. Think about what’s happening in Gaza. And we have religious wars between Shia and Sunni within Islam. Think of the long struggles between Iran and Saudi Arabia for dominance in the world of Islam – struggles in which we are constantly being caught up. These conflicts are heartbreaking.

But I’m also finding myself thinking there is a possibility of religious war here in the United States. Some of this mirrors those global conflicts, but more to the point it involves conflicts among Christians, and between some Christians and others who do not consider themselves religious at all.

1648. That’s a date I don’t imagine many of you ever think about. It’s the year the great religious wars in Europe ended. It was the conclusion of what we came to call the Thirty Years War, but it was really a war that lasted longer than that.

The Thirty Years War was a long, extremely bloody struggle to decide what was the one true religion – the one, true religion that everyone should believe and practice – to achieve that universal agreement bon big questions. It was largely between Roman Catholics and Protestants, though sometimes also between different kinds of Protestants. Each side tried to impose its understanding of the one true religion on everyone else. Our understanding of sin. Our understanding of baptism and communion. Our understanding of marriage.

This was an appalling war. The International Red Cross estimates that between 4 and 12 million people lost their lives from combat, or from resulting disease or famine. Perhaps 20% of the population of Europe died.

The Thirty Years War ended in a stalemate, a very bloody stalemate. Exhausted and appalled at the carnage, the various kings and princes and Dukes of Europe agreed that each country would have whatever religion its king or prince or duke decided, and that the various countries would no longer try to impose their religion on others. These wars ended in 1648 with the signing of the Treaty of Westphalia.

This wasn’t yet religious liberty as we know it today – the kind of religious liberty that we celebrate in the First Amendment. After 1648 Kings could still impose the one true religion on those in their own country. And they did. But they agreed not to try to impose across national borders.

Nevertheless, it wasn’t many decades before countries began to agree that there wouldn’t be religious war within their own boundaries. They began to agree that each person could worship God as he or she saw fit (or not worship at all). They began to agree that governments wouldn’t say this is the right way, the only way allowed. It wasn’t so far and so long from The Thirty Years War to the First Amendment, from the one true religion to religious liberty.

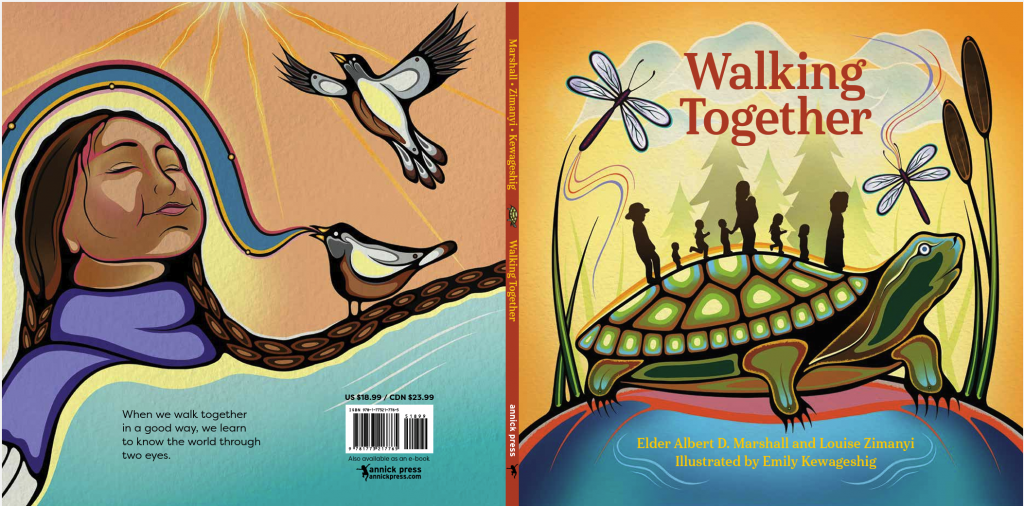

Aren’t I talking politics here in Meeting? Yes, but I’m also talking religion. The beginnings of Quakerism are deeply connected to this search for religious liberty. Remember we’re the religious group without a creed, without an authoritative statement of belief. We’re a religious group whose beliefs and practices disturbed many people.

Let’s come back to 1648, the Treaty of Westphalia. It was just four years after that date that George Fox climbed Pendle Hill and had his epiphany: Christ would speak to him if he stilled himself to listen. And that very same year Fox preached to over a thousand people at Firbank Fell beginning the movement we call Quakerism.

The beliefs and practices of Quakers were deeply offensive to the leaders of the Church of England. I think we can lose track of that. Fox was imprisoned and more than once. Dozens, hundreds of other Quakers were imprisoned. Some died. Why? Because Quakers wouldn’t go the local Church of England church. They wouldn’t take off their hats to nobility. They used “thee and thou” with everyone. They believed they didn’t need priests. They wouldn’t swear oaths. They wouldn’t recite the creeds of the Church of England. They wouldn’t fight in wars. They allowed women to preach. All these upset people in the established church.

In those first decades of Quakerism, it was perilous to be a Quaker. It took secrecy or courage – or both. Not until the Petition of Right, in 1685, was there even a modest measure of individual religious liberty in Britain.

We all know the stories of people coming to the American colonies for religious liberty. Often, however, they created communities where there was one true religion, their own, and they persecuted others. In 1660, Mary Dyer was hanged in Boston, in Massachusetts Bay Colony, for repeatedly defying a Puritan law banning Quakers from the colony.

We might think those days are long in our past. After all I’ve mostly been talking about the 17th century. But here in the 21st century, some of our most difficult conflicts involve abortion, sexual orientation and gender identity, and attitudes toward those with different religious beliefs, Muslims or Jews or Sikhs. We’ve come to call these “social issues,” but they are very much like religious ones. They involve beliefs about “the right way to live.” These are conflicts fueled by strong beliefs about what is sinful and what is not: like abortion, like sexual identity. I fear we are slipping back into a time of religious war.

We often talk about the religious freedom part of the 1st Amendment to the Constitution as “Separation of church and state.” Those aren’t the words of the Amendment, though. The Amendment really has two parts. It says there shall be “no establishment of religion.” That means no official church. No one is compelled to have any particular beliefs or practices, and no church is given special status.

And the Amendment also says (this is the second part) that there shall be “no prohibiting the free exercise of religion.” That means each person can have whatever beliefs they choose or use whatever worship practices they choose.

“No establishment of religion” and “free exercise”. Those two principals have defined what religious freedom has meant in the United States since our founding. They are bookends. And they are simple, aren’t they? No, not really. Both principles are open to a good deal of interpretation. And we are finding ourselves again in a time when the current interpretations are being challenged.

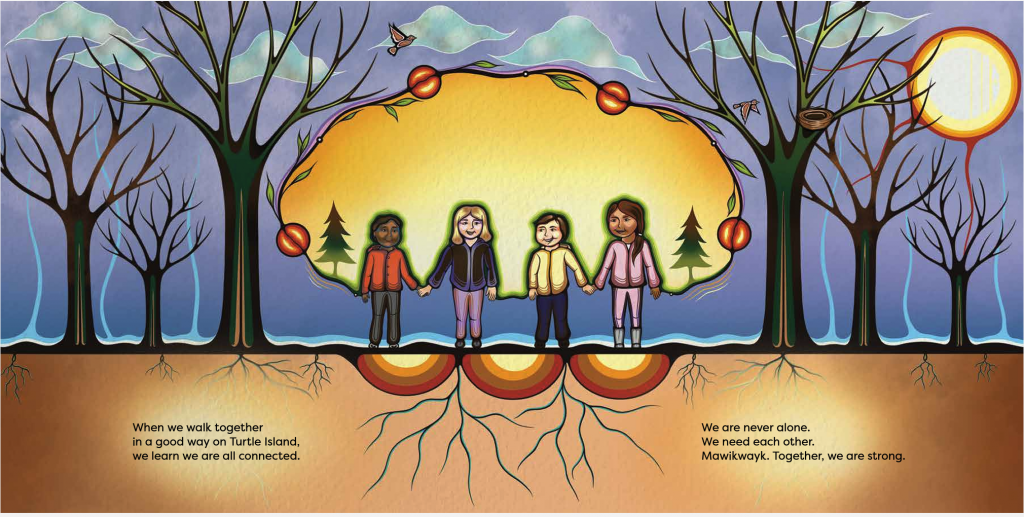

“Tolerance” is another way to talk about these two principles. ‘You go your way and I’ll go mine.’ ‘You worship as you please and I’ll worship as I please.’ We can try to persuade one another, but we won’t try to coerce others into sharing our beliefs or our practices. It’s a way to avoid conflict over deep beliefs. “Tolerance” is a basis for living together with people with whom we disagree – with whom we disagree about the most important matters.

“Tolerance” is a good thing, or so we’ve long thought. Quakers have valued it because tolerance has allowed us to have our unusual practices without being thrown in jail.

We should recognize, however, that “tolerance” is a second-best solution. Wouldn’t it be better if we all agreed? Wouldn’t it be better if we all shared the same beliefs and practices? Wouldn’t that be best? I think we’d all rather live in harmony with people in a situation where no one did things that horrified or disgusted anyone else. But is we cannot have that, tolerance is second best, and the best humans can achieve.

Such harmony can be hard to achieve. We found that out in the 17th century in a very deadly, bloody war. And it seems like some people are aching again for that first best solution: everyone agrees, and we use the law and coercion to insist that everyone agrees.

Nevertheless, if we want everyone to agree, the only way to achieve that is likely through coercion, conflict and war. Think about that when you hear someone say this or that is the only right way to live, or you hear someone say that this or that practice should be outlawed. Think about that when you hear someone speak of the U.S. as “a Christian nation,” and men by that their own particular brand of Christianity.

If we don’t want that, if we don’t want religious war, tolerance is the way to live together. We’ve been here before. Tolerance doesn’t mean we give up having our beliefs and our practices. It simply means we give up trying to coerce others to follow our beliefs or our practices. We can try to persuade people, but not coerce them.

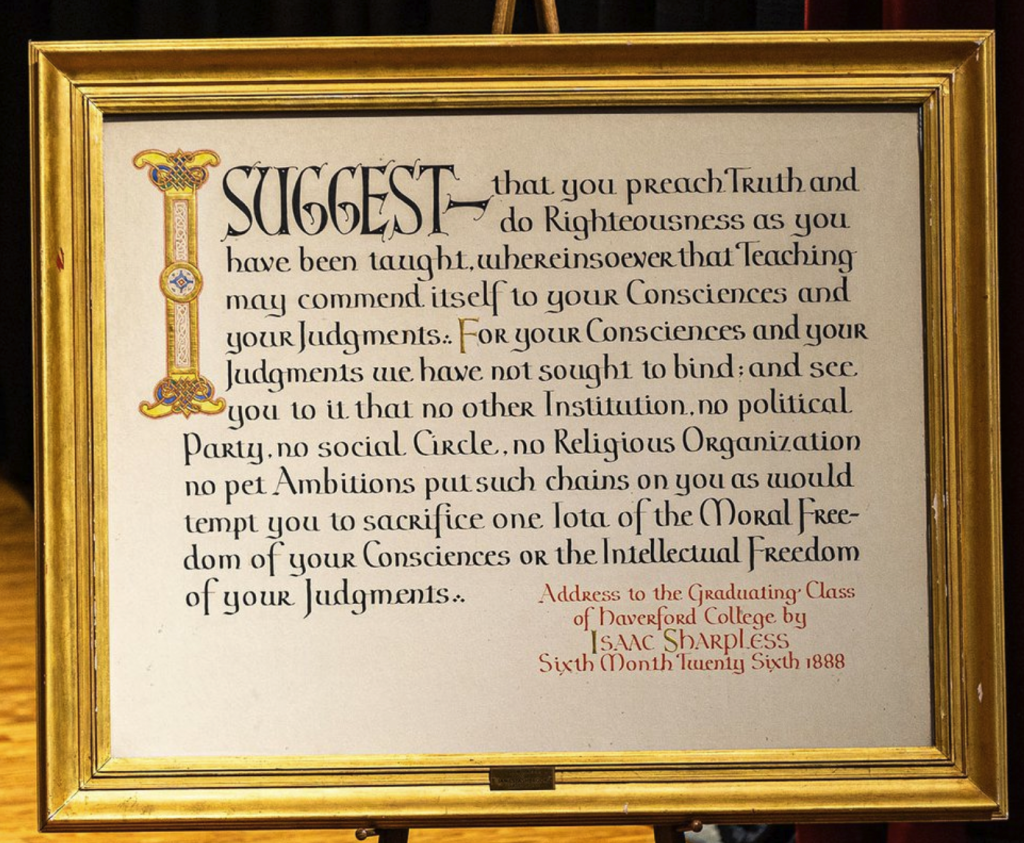

As William Penn says, ““Let us then try what love can do to mend a broken world.”