Message given by Jane Field of the Maine Council of Churches at Durham Friends Meeting, May 1, 2022

I bring you greetings from the Maine Council of Churches, where I serve as the Executive Director. We are an ecumenical coalition of seven Protestant denominations in the state, including yours, the Religious Society of Friends. Together, we have 441 congregations with more than 55,000 members who live out their faith in towns from Kittery to Fort Kent, from Rumford to Eastport. The Quaker representative who sits on our Board is Diane Dicranian; a member of your Meeting, Cush Anthony, is an at-large member of the Board; and we work with the Clerk of the New England Yearly Meeting, Bruce Neumann, and consult with him on major issues before the Council. In fact, we are the grateful recipients of a Prejudice and Poverty Grant from the Yearly Meeting that is funding our upcoming event in Brunswick, “Saying Peace, Peace When There Is No Peace: How Demanding Civility Risks Protecting White Privilege,” next Thursday, May 5, from 11am to 1pm in-person at the UU Church and streaming online—we hope you’ll join us!

Your own Leslie Manning almost single-handedly held the Council together during some difficult days of restructuring about 10 years ago, and continued to serve on our Public Policy Committee for years after the boat stopped rocking. Another Quaker in MCC’s Hall of Fame is Tom Ewell, who served as Executive Director in the 80’s and 90’s and remains on my speed dial even today as a trusted colleague and faithful supporter of the Council.

We are a small (but scrappy!) nonprofit organization whose mission is to inspire congregations and Mainers of faith and goodwill to unite in working for the common good, building a culture of justice, compassion and peace, where peace is built with justice and justice is guided by love. We carry out that mission by offering statewide educational programs and resources, and through faith-based legislative advocacy in Augusta—promoting policies that:

- Reduce poverty, hunger and homelessness

- Protect and restore the environment

- Increase equitable access to health care and education

- Defend the rights and dignity of the vulnerable and marginalized (particularly LGBTQ+ and New Mainers, people of color, and our Wabanaki tribal neighbors)

- And ensure that Mainers can live together harmoniously with equity, peace, and safety for everybody.

If you would like to learn more about our work, you’re welcome to take a copy of our most recent newsletter or visit our website (mainecouncilofchurches.org). You can sign up to receive our newsletters and emails—either via our website, our Facebook page, or by phone.

You could say that we at the Maine Council of Churches are all about making connections—and this morning I’d like us to spend some time thinking about how and why God’s dream is for us to be … connected.

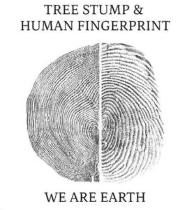

We’re going to do that by looking at the hidden life of trees. That’s the title of a wonderful book by Peter Wohlleben, a forester who works deep in the forests of Germany, and who has learned astonishing things about trees—trees just like the ones outside this building, just like the ones in your own backyards. As I describe his extraordinary findings, I invite you to think about a favorite tree of yours (we all have one, don’t we? Mine is a Japanese pine that stands at the water’s edge near my family’s camp; my whole life it has been framed perfectly in the camp’s picture window that looks out on the lake).

Picture your tree’s trunk. Did your mind’s eye automatically look up? Now look down to where your tree’s trunk meets the earth, and let your imagination envision the intricate root systems that are lying underground below your tree.

In his book, Wohlleben describes something miraculous going on in those roots that we humans can neither see nor hear: trees are communicating with one another. He has discovered they depend on a complicated web of cooperative, interdependent relationships, alliances and kinship networks. Wise old mother trees feed their saplings and warn neighbor trees when danger is approaching. Reckless teenagers take foolhardy risks chasing the light and drinking excessively, and usually pay with their lives. Crown princes wait for old monarchs to fall, so they can take their place in the full glory of sunlight. It’s all happening in the ultra-slow motion that is tree time. [Smithsonian, “Do Trees Talk to Each Other?” by Richard Grant, March 2018]

A revolution has been taking place in the scientific understanding of trees, and the latest studies confirm what Wohlleben and his colleague Suzanne Simard of British Columbia have long suspected: Trees are far more alert, social, sophisticated—and even intelligent—than we thought. There is now scientific evidence showing that trees of the same species are communal, and often form alliances with trees of other species, too, living in cooperative, interdependent relationships, maintained by communication and a collective intelligence similar to an insect colony.

These soaring columns of living wood draw our eyes upward, but the real action is taking place underground, just a few inches below our feet. Wohlleben jokes that we could call this underground communication network “the ‘wood-wide web.” It connects trees to each other through a web of roots and fungus. Trees share water and nutrients through the network, and also use it to communicate. They send distress signals about drought, disease, or insect attacks, and other trees alter their behavior when they receive these messages.

Scientists call these “mycorrhizal” (my-core-eyes-all) networks. The fine, hairlike root tips of trees join together with microscopic fungal filaments to form the basic links of the network. Trees pay a kind of fee for network services (like a cable or cell phone bill!) by allowing the fungi to consume about 30 percent of the sugar that the trees photosynthesize from sunlight. The sugar is what fuels the fungi, as they scavenge the soil for mineral nutrients, which are then absorbed and consumed by the trees. One teaspoon [hold up a teaspoon] of forest soil contains several MILES of these fungal filaments!

For young saplings in a deeply shaded part of the forest, the network is a lifeline. Lacking the sunlight to photosynthesize, they survive because big trees, including their parents, pump sugar into their roots through the network. For elderly trees, it serves as nursing care. Once, Wohlleben came across a gigantic beech stump, four or five feet across. The tree was felled 400 or 500 years ago, but scraping away the surface with his penknife, he found something astonishing: the stump was still green with chlorophyll. There was only one explanation. The surrounding beeches were keeping it alive, by pumping sugar to it through the network. “When beeches do this, they remind me of elephants,” he says. “They are reluctant to abandon their dead, especially when it’s a big, old, revered matriarch.”

To communicate through the network, trees send chemical, hormonal and slow-pulsing electrical signals, which scientists are just beginning to decipher. Some trees may also emit and detect sounds, a crackling noise in the roots at a frequency inaudible to humans.

Trees also communicate through the air, using pheromones and other scent signals. In Africa, when a giraffe starts chewing acacia leaves, the tree notices the injury and emits a distress signal in the form of ethylene gas. Upon detecting this gas, neighboring acacias start pumping tannins into their leaves. In large enough quantities these compounds can sicken or even kill large herbivores—like giraffes. (Giraffes are aware of this, however, having evolved with acacias, and this is why they browse into the wind, so the warning gas doesn’t reach the trees ahead of them. Giraffes seem to know that the trees are talking to one another!)

Trees can detect scent and taste through their leaves. When elms and pines come under attack by leaf-eating caterpillars, they detect the caterpillar saliva, and release pheromones that attract wasps who lay their eggs inside the caterpillars. The wasp larvae eat the caterpillars from the inside out. “Very unpleasant for the caterpillars,” says Wohlleben. “Very clever of the trees.”

A recent study shows that trees recognize the taste of deer saliva. When a deer is biting a branch, the tree brings defending chemicals to make the leaves taste bad so the deer will stop. If, on the other hand, a human breaks the branch, the tree knows the difference, and brings in substances to heal the wound.

Why do trees share resources and form alliances with trees of other species? Doesn’t the law of natural selection—“survival of the fittest”—suggest that they should be competing? “Actually, it doesn’t make evolutionary sense for trees to behave like resource-grabbing individualists,” botanist Simard says. “They live longest and reproduce most often in a healthy stable forest. That’s why they’ve evolved to help their neighbors.”

But this isn’t a high school biology class—why talk about this in a worship service? I can think of at least two reasons. The first is just the sheer miracle of it all—how amazing is God’s creation?!

The second reason to talk about this in worship is because it is a beautiful metaphor from nature about how we are meant to exist in community, especially within the church, both at the local level, and in the broader, wider church, as we are, you and I, through the Maine Council of Churches. We are meant to be connected, just like trees are. We, too, are meant to love and help our neighbors. As Paul taught the Corinthians, “If one member suffers, all suffer together with it; if one member is honored, all rejoice together with it.”

It is our hope and prayer at the Council that we can be a sort of “mycorrhizal network” connecting local congregations like yours here at Durham Meeting with others all around the state. Like trees who are connected through vast root systems, we can share what nourishes us. We can send distress signals when someone among us is in danger or under attack so that all of us can rally around and take action. We can look out for young ones and our elders, and we can learn from each other.

Because, like trees, it doesn’t make evolutionary sense for us to behave “like resource-grabbing individualists,” either. We, too, live longest and best in a healthy, stable “forest”—a community where we love our neighbors, even as we love ourselves.

So this morning, while I am here as your guest, let us give thanks for the “mycorrhizal” system that connects us to each other, to the wider faith community (including the Maine Council of Churches), and to our neighbors of every faith, a system that connects us to creation, and to God. Let us celebrate how we, like the trees, thrive in a network of trust, shared language, and deeply interdependent relationships that are shaped by faith, hope and love, justice, compassion and peace. May it be so. Amen.