Message given at Durham Friends Meeting, March 8, 2025

Older than the Declaration of Independence. Older than the United States of America.

That’s how old this Meeting is. Founded in 1775, this is our 250th year as a Quaker Meeting. The Declaration of Independence won’t have it’s 250th anniversary until next year.

Since before there was a United States; 45 years before there was a Maine, we Friends have been worshipping together in this corner of Durham, regularly and faithfully, week in and week out for 250 years. That is 13,000 1st Days. I bet we have not missed many. This year is our Anniversary. It is an occasion for celebration.

We celebrate anniversaries: birthdays, wedding anniversaries, deaths of prominent people and loved ones, important dates in history. Our 250th Anniversary is notable, and not just to those who worship here. It is notable, too, for Durham, for the residents of Midcoast Maine, for New England Yearly Meeting, and for Quakers everywhere. But it is especially important for us who worship here now – in the present and in the future.

As we look back across the years, we remember many individuals who have been part of this Meeting, helped shape it and sustain it.

We remember individuals who were part of the life of this Meeting, no longer with us: Margaret Wentworth, Sukie Rice, Bobbie Jordan, Louis Marstaller, Clarabel Marstaller, Macy Whitehead, Eileen Babcock, Bea Douglass, Kitsie Hildebrandt, Charlotte Ann Curtis, Helen Clarkson, Sue Wood, Phyllis Wetherell. No doubt you can think of others, and think, too, of the dozens and dozens of others who passed away enough years ago that no one of us present today has specific memory of them. They, too, are part of our story. The earthly bodies of many of these Friends are interred in the cemeteries we maintain.

For many decades we had pastors, and we remember them: Ralph Green, Jim Douglass, Daphne Clement, Doug Gwyn – and many more.

Some left bequests to the Meeting that make possible what we do today: Woodbury, Bailey , Pratt, Cox, Pennell, Goddard, Douglass, Babcock. Those funds are a kind of inheritance from the past, and they help fuel our present. In parts near and far there are quilts that have been sewn to welcome babies to this world.

Our beloved Meeting house is another kind of inheritance. We first built a Meetinghouse on this site in 1790, and another in 1800. This current brick Meetinghouse, our third on this site, dates from 1829. It, too, is a gift from the past that sustains our Meeting today.

We should make our marking of this anniversary in this year a time of remembering people and events that have shaped us.

There is a great deal about the history of this Meeting that I do not know. Much of it can probably be learned from the Minutes we have faithfully kept. We do, however, know some of the large context.

Here is one way to mark the 250 years. Friends gathered in worship here during the American Revolution, the War of 1812, the Mexican-American War, the Civil War, the Spanish American War, the First World War, the Second World War, the Korean War, the Cold War, the Vietnam War, the endless recent wars. Through all these wars, we have prayed for understanding, for mercy and for peace. Over these centuries we have cared for our members in times of trouble, and assisted our neighbors.

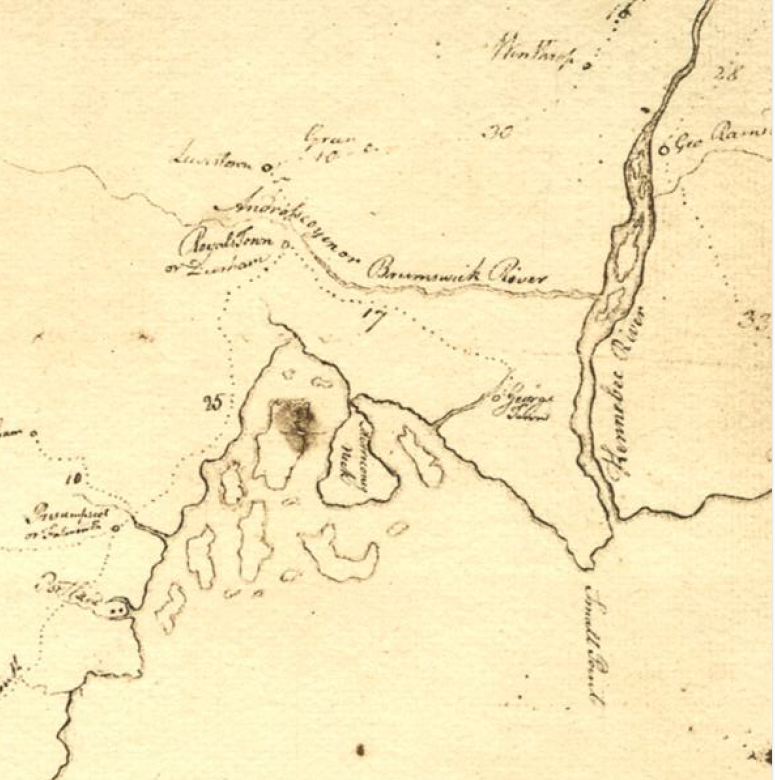

For centuries, this place has been the home of the Abenaki. The placed we call Maine, today, was further settled by European immigrants as part of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Over the course of the 1600s and early 1700s, these settlers displaced the indigenous Abenaki. By disease, by swelling numbers of immigrants, and sometimes by violence, the Abenaki were pushed aside and away. We remember that the Abenaki were here first, and we should.

Over that very same course of time, 1650 or so to 1750, the religious movement we call Quakerism was coming to life, first in England but spreading quickly beyond England. In 1642, in the midst of the English Civil War — a religious war between Protestants and Catholics — George Fox had his epiphany on Pendle Hill. He realized God would speak to him in the present. He gathered others and they created a movement: “primitive Christianity revived.” Less than two decades after Pendle Hill there were Quakers in what is now Rhode Island. Fox visited the Americas in the 1670s.

The first Quaker Meeting in what is now Maine took place about 1730, in what is today Berwick. Midcoast Maine, where we are, was beset by strife and war between colonial settlers and native Americans until about 1770. When that quieted down, our Meeting began in 1775. Farmers came here from Harpswell and from southern Maine. Their first Meetings were held in the log houses they built. There is just 130 years or so from the epiphany on Pendle Hill to the founding of Durham Friends Meeting – about half the number of years that follow from the founding of this Meeting to today. For two-thirds of the time there has been Quakerism anywhere, there has been Quaker worship at Durham Friends Meeting.

It is right we think of the Declaration of Independence when we think of the year of our founding. Quakers in New England and this Meeting: we were established in strivings for religious reform and religious liberty.

The first European-style religious organization in these parts was the Congregational Church, the established church of Massachusetts Bay Colony. The first religious service of these Congregationalists of which we have record was in 1717, and took place outdoors at the falls between Brunswick and Topsham.

Religious freedom as we know it was not respected here at that time. There was an official religion, and everyone was expected to follow its ways. It was not OK in Massachusetts Bay to be anything other than a Puritan (a Congregationalist). Roger Williams was driven out of Massachusetts Bay in 1636. Ann Hutchinson was driven out in 1637. The Quaker Mary Dyer was hanged on Boston Common in 1660 – hanged for preaching “the diabolical doctrines” of the “cursed sect of Quakers.”

So far as we know, the coming of Quaker worship in Royalsborough (now called Durham) in 1775 was just the second such European-style religious organization to begin services here in this area – and therefore the first non-Congregationalist organized worship. We Quakers were a feisty bunch, the religious renegades – the independents.

Freedom of religion was not officially recognized in Massachusetts until 1780, a few years after we began. After 1780 other denominations entered the picture. The Baptists began to worship in these parts in 1783, Universalists in 1812, Methodists in 1821, Unitarians in 1829, Episcopalians in 1842, and Roman Catholics about 1860.

In our early years we helped spread the Quaker manner of worship more widely in Maine. The Hattie Cox history from 1929 says this Meeting “mothered groups of Friends in Lewiston, Greene, Wales, Leeds, Wilton, Pownal and Litchfield.”

Quakerism has not been an unchanged or unchanging thing during all these years. At times we have adopted new ways, smoothly. At other times, not so much. There used to be separate entrances to this very Meetinghouse for women and for men, and a sliding wall that allowed them to meet together or separately. Some of you can remember when the benches were rearranged into a square. At other times there have been schisms. When Elias Hicks and his followers divided American Friends (especially in Philadelphia and Baltimore) in the 1820s, we stayed with the Orthodox Friends, as did most of New England Yearly Meeting.

In the middle of the 19th century, when Englishman Joseph John Gurney preached evangelical zeal to American Friends, this Meeting with many others in our Yearly Meeting followed the Gurneyite path, while others, those we call Wilburites, stayed with the older ways. In time, that Gurneyite path brought us hymn singing and later brought us to have pastors. We did not used to have hymn singing or pastors.

Through the years there has been a Religious Society of Friends, Quakers have alternated between two modes. Sometimes we separate ourselves a bit from the world and try to live on our own terms keeping to our own ways. At other times, we have seen our ways as something to try to spread to others both through ministry and through social action. This Meeting has had periods of both, but today, you all know, we are very much of a ‘spreading our ways to others’ inclination.

Today, we are simultaneously a place of spiritual worship and support and a hub of activism. That activism has many faces: a food ministry through Tedford and LACO, opposition to gun violence, social justice education for the young, welcoming assistance to migrants, support for Native American causes, affirmation of same-sex relationships, prison reform, connection to Cuba Yearly Meeting. We take guidance from AFSC and FCNL. This is a great deal for a numerically small Meeting.

An anniversary is a time to remember and be grateful for the past. It is also a time to take stock of the present situation, and then to recommit ourselves, as a Meeting.

In our current circumstances, I find myself thinking of what Lincoln said to the Congress in 1862: “The dogmas of the quiet past, are inadequate to the stormy present. The occasion is piled high with difficulty, and we must rise — with the occasion. As our case is new, so we must think anew, and act anew. We must disenthrall ourselves, and then we shall save our country.” Our anniversary is a time for fresh thinking about who we are and what we want to do together.

We are a smaller Meeting today than we have been for much of our history. Still, we are a sturdy Meeting, one filled with remarkable people. I look around this room each Sunday and I see many Friends who are deeply faithful and also deeply engaged in making the world better. I see individuals who do the work of many. Our numbers may be fewer, but the presence is astonishing.

There is a future before us, and we all hope a 300th anniversary, and a 350th, and on and on. It is our future to make.

What’s most important, for me at least, is that here in Durham, at this place, there continues to be worship every First Day after the manner of Friends. “After the manner of Friends”: I don’t mean that in any formalistic way. I don’t mean we have to open with a hymn and close with announcements and a hymn. I mean rather that each time we gather we are alert to what God has to say to us now. That is our most important inheritance, and also our gift to the those yet to come: the confidence that God is speaking to us today, the faith that God will speak to us when we still ourselves and listen.

Also posted on River View Friend